Adolescents have such power and potential. They can achieve so much when they have a supportive space that helps them develop their incredible abilities and ultimately realize their possibilities.

The book, The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults, shares a helpful analogy for understanding adolescence: “...the teenage brain is almost like a brand-new Ferrari: it’s primed and pumped, but it hasn’t been road tested yet. In other words, it’s all revved up but doesn’t quite know where to go.”

To best support adolescents who are all primed to go but don’t yet know where, we can work to better understand their developmental characteristics and needs.

Time of Transformation

The first three years (ages twelve to fifteen) of adolescence are comparable to the physical and cognitive transformation that happens from zero to three. Adolescents are forming themselves, physically and psychologically, into the adults they will become.

This is a transition from childhood into adulthood, evidenced by dramatic bodily changes. The relative calm and stability of the previous years shifts to a more tumultuous time. During this period of intense change, adolescents’ health becomes more fragile. They require more sleep and are more prone to acne, depression, bulimia, anorexia, mono, etc. As Frances E. Jenson, MD, and Amy Ellis Nutt explain in The Teenage Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Survival Guide to Raising Adolescents and Young Adults: “Adolescence is a time of increased response to stress, which may in part be why anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, typically arise during puberty. Teens simply don’t have the same tolerance for stress that we see in adults. Teens are much more likely to exhibit stress-induced illnesses and physical problems, such as colds, headaches, and upset stomachs. There is also an epidemic of symptoms ranging from nail biting to eating disorders that are commonplace in today’s teens.”

Adolescents need a special kind of care and protection during this time of transformation. Like caterpillars that need a chrysalis in order to metamorphose into a butterfly, adolescents need a protective space for reconstruction.

Neural Changes and Emotional Needs

The adolescent brain is also undergoing dramatic changes, from neural pruning when unneeded neural synapses are removed, to an increase in myelination which allows for faster neural transmission.

Due to these dramatic physical and cognitive changes taking place, adolescents can have difficulty concentrating and staying focused. This also leads to a decrease in their organizational skills and judgment, as well as a reduction in their executive functioning abilities like working memory, flexible thinking, and self-control. Because of this diminished executive functioning ability, adolescents often make decisions based on emotion. Their brains are relying upon the limbic system rather than their developing prefrontal cortex.

Thus, adolescents can experience strong and tumultuous emotions and it can be a struggle for them to gain mastery over these emotions. As such, adolescents need time for personal self-reflection, and yet this need exists in the midst of an intense desire to be within and accepted by a group.

Rational and logical expression can be challenging during this time, thus adolescents also need creative outlets for releasing and exploring emotions, thoughts, and any conflicting experiences. Creative outlets can include dance, writing, art, music, sports, etc. In addition to providing an expressive outlet, physical activities also release endorphins and help regulate hormonal balance.

Finding Equilibrium

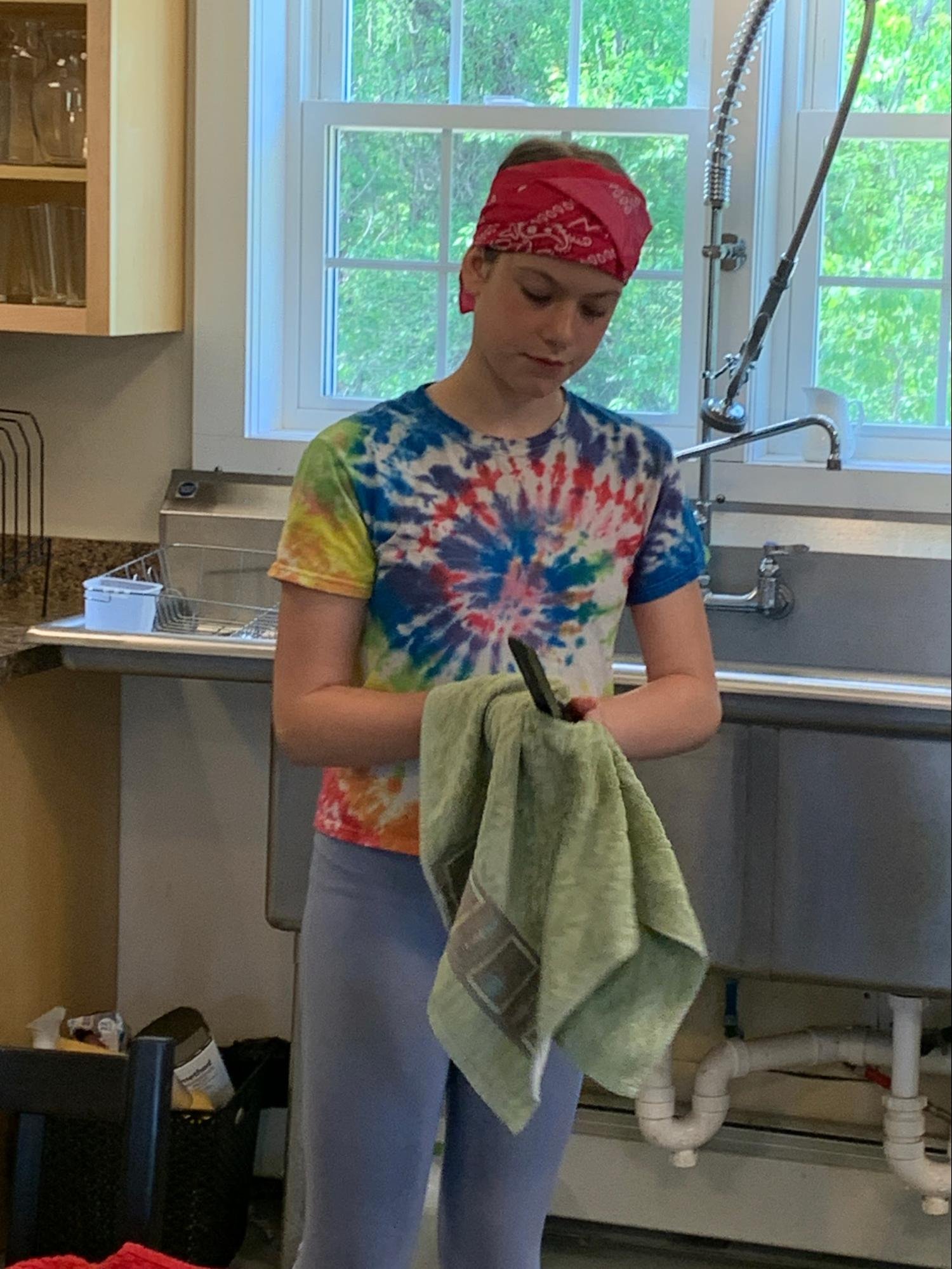

Because adolescents are working to integrate their new physical and emotional selves, they need as many opportunities as possible to integrate manual work (work of the hand) and academic work (work of the head). In addition to experiencing an equilibrium in mental and physical activities, adolescents need opportunities to explore their personal identity in the context of their social identity.

Like younger children, adolescents are somewhat ego-centric. After leaving the elementary years of calm and confidence, early teens become self-conscious and are highly sensitive to peer acceptance. This results in a sensitivity to the looks, comments, or actions of others, which is further complicated by adolescents having difficulty reading facial expressions. It’s no surprise, then, that our teens often imagine that someone is upset with them or thinking negatively of them. Close relationships and feeling accepted by their peer group become extremely important to balance these feelings.

Being Valued

Because this is a time of extreme vulnerability, adolescents need to be treated with understanding and respect. They want to know their value, their role, their contributions, and their worth. Adolescents benefit greatly from opportunities to contribute to their community in meaningful ways. This is best achieved through adult-level work. When this contribution is acknowledged by their peers, adolescents feel valorized, or recognized, which leads to a bolstering of their self-confidence.

Having choices is also a vital component of adolescents’ work. This opportunity to make a choice about what to do and when to do it provides teens with a strong sense of empowerment and allows them to practice making constructive choices.

Role of Adults

Adolescents need the guidance and support of adults. They also rely upon and appreciate the opportunity for side-by-side work. We can shift into more of a supportive, coaching role with our adolescents, which can more easily be achieved when we are working alongside each other. Adolescents relish this opportunity to collaborate in what it means to be an adult by engaging in adult-level work.

This side-by-side work also offers us, as adults, the opportunity to respectfully share information and teach skills, without risking offending our adolescents. In “Three Ways to Change Your Parenting in the Teenage Years,” Christine Carter explains: “When we give our adolescents a lot of information, especially when it is information that they don’t really want or that they think they already have, it can feel infantilizing to them. Even if we deliver the information as we would to another adult, teenagers will often feel disrespected by the mere fact of our instruction.”

Respectful treatment connects to adolescents’ need to feel a sense of justice and personal dignity. While elementary-aged children focus on distributive justice (e.g. fairness), adolescence is a time when young people begin to grapple with and understand restorative justice, social justice, and economic justice.

Adolescence is a period of dramatic growth and change. Although the dramatic physical changes that accompany the onset of puberty can rock the stable foundation of elementary years, if we understand adolescents’ needs, we can help our teenagers emerge as empowered and full of creative energies.