One hallmark of a Montessori education is the use of multi-age classrooms. Infants and toddlers may be together or separate, with a toddler classroom serving children 18 months to three years. Primary classrooms are for children ages 3-6, with preschool and kindergarten-aged children together. The elementary years serve children ages 6-12; some schools separate into lower (6-9) and upper (9-12) elementary, while many split elementary into two groups. Even Montessori middle- and high-school students learn in multi-age classrooms.

While Montessori is not the only type of education that utilizes this approach, it’s not what most people are used to. What are the benefits of structuring a classroom this way? Read on to learn more...

Learning at an Individual Pace

Children in multi-age classrooms tend to have a little more flexibility when it comes to mastering skills within a specific timeframe. We know that learning is not linear, and that learners have periods of significant growth, plateaus, and even the occasional regression. In multi-age classrooms, children are typically able to work at their own pace without the added pressure of keeping up with the whole group, or even being held back by the whole group.

When children in a classroom range in ages, everyone has someone they can work with, regardless of their skill level. Children don’t feel left behind if they struggle with a concept, and they also don’t feel bored by repetition of something they have already mastered. Teachers who teach in multi-age classrooms typically have deep knowledge for a range of developmental abilities, leaving them well-equipped to differentiate instruction for each individual child.

Building Stronger Relationships

Traditionally children move from one class to the next each year. This means not only a new set of academic expectations, different routines, and different classroom structures, but a different teacher.

In multi-age classrooms teachers have a longer period of time to get to know a student and their family, and vice versa. When teachers really get to know a student, they are able to tailor instruction in regards to both content and delivery. They know how to hook a specific child onto a topic or into a lesson. They know what kind of environment a child needs to feel successful.

Parents have an opportunity to get to know teachers better this way, too. If your child has the same teacher for two or three years, the lines of communication are strengthened. Parents get to know the teacher’s style and expectations. The home to school connection becomes more seamless, and the biggest beneficiary is the child.

Mentors and Leaders

When a child spends multiple years in the same class they are afforded two very special opportunities.

Children who are new to the class are fortunate enough to be surrounded by helpful peer mentors. Children often learn best from one another, and they seek to do so naturally. First and second year students watch as the older children enjoy advanced, challenging work, and this inspires them. They look to the older children for guidance, and the older children are happy to provide it.

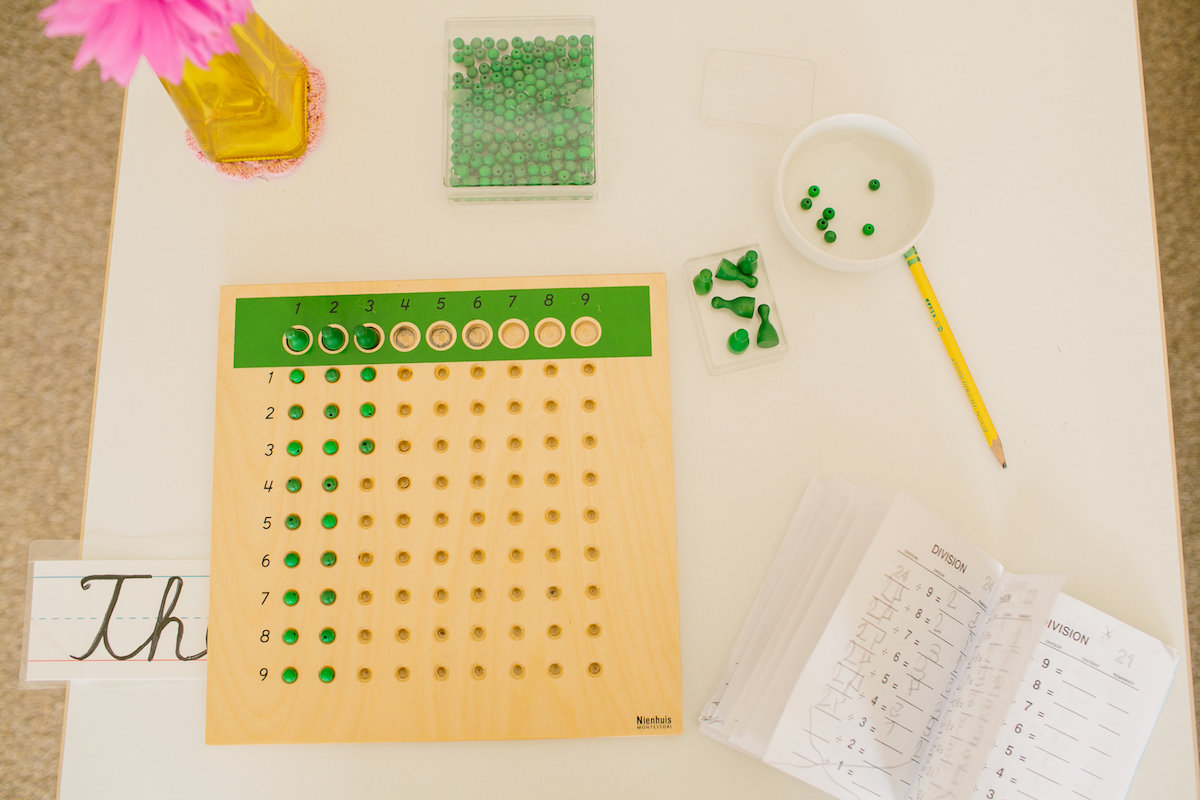

After a year or two in the same room, students have a chance to practice leadership skills. In Montessori classrooms, the older children are often seen giving lessons, helping to clean up spills, or reaching out a comforting hand to their younger friends.

The best part is kids make the transition from observer to leader in their own time. It doesn’t happen for all children at the same time, but when it does it’s pretty magical to observe.

Mirroring Real-Life

There is no other area in life in which people are split into groups with others who are exactly their chronological age. Whether in the family, the workforce or elsewhere, people ultimately need to coexist with people older and younger than themselves. Doing so makes for a more enriching environment, replete with a variety of ideas and skills.

Why not start the experience with young children in school?

Moving On

While staying in the same class for multiple school years has many benefits, a child will eventually transition into a new class. While this can feel bittersweet (for everyone involved!) children are typically ready when it is time.

The Montessori approach is always considering what is most supportive of children depending on their development. When formulating how to divide children into groupings, Maria Montessori relied on her ideas about the Planes of Development. There are very distinctive growth milestones children tend to reach at about age 3, another set around age 6, and yet another at age 12. The groupings in our schools are intentional, and they give kids a chance to feel comfortable in their community, while also preparing them to soar forward when the time is right.