This is not a news flash:

Handwriting instruction is disappearing in schools across the United States.

You’ve probably already heard this sad revelation, and while it’s certainly not true for all schools, more and more are eschewing handwriting instruction to make more time for other, standards-based skills. The result is a generation of children who are not gaining a sense of how important it is to be able to write beautifully and they are simply not learning cursive – period.

If this makes you cringe, here’s the good news: people are noticing and speaking up, and some schools are finding ways to fit handwriting back into the schedule. Even better news? Montessori schools never dropped it in the first place. Read on to learn more about how this 100+ year-old educational approach guides children in the art of writing beautifully.

Indirect Preparation

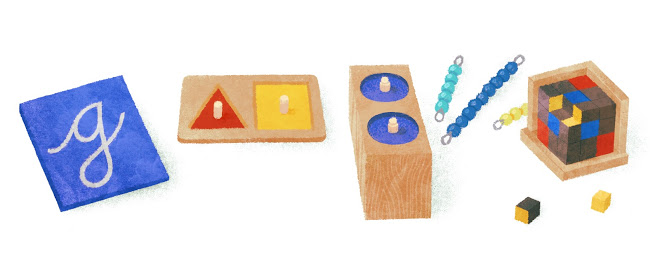

If you walk into a Montessori toddler or primary classroom, you will see very young children working with materials that develop fine motor skills. While fine motor proficiency can serve children in a wide variety of ways, Montessori intentionally created materials that strengthen the hand as indirect preparation for handwriting.

Each time a three-year-old lifts a knobbed cylinder they are developing proper pincer grip. This same action is repeated in many other materials. The child may be working to joyfully refine a sensorial skill, but at the very same time their tiny fingers are slowly working their way toward being able to hold a pencil correctly.

Many Montessori materials are designed to be used working from left to right in order to prepare the child to move in that direction while writing. Even the materials themselves are organized in a left to right fashion on the shelves.

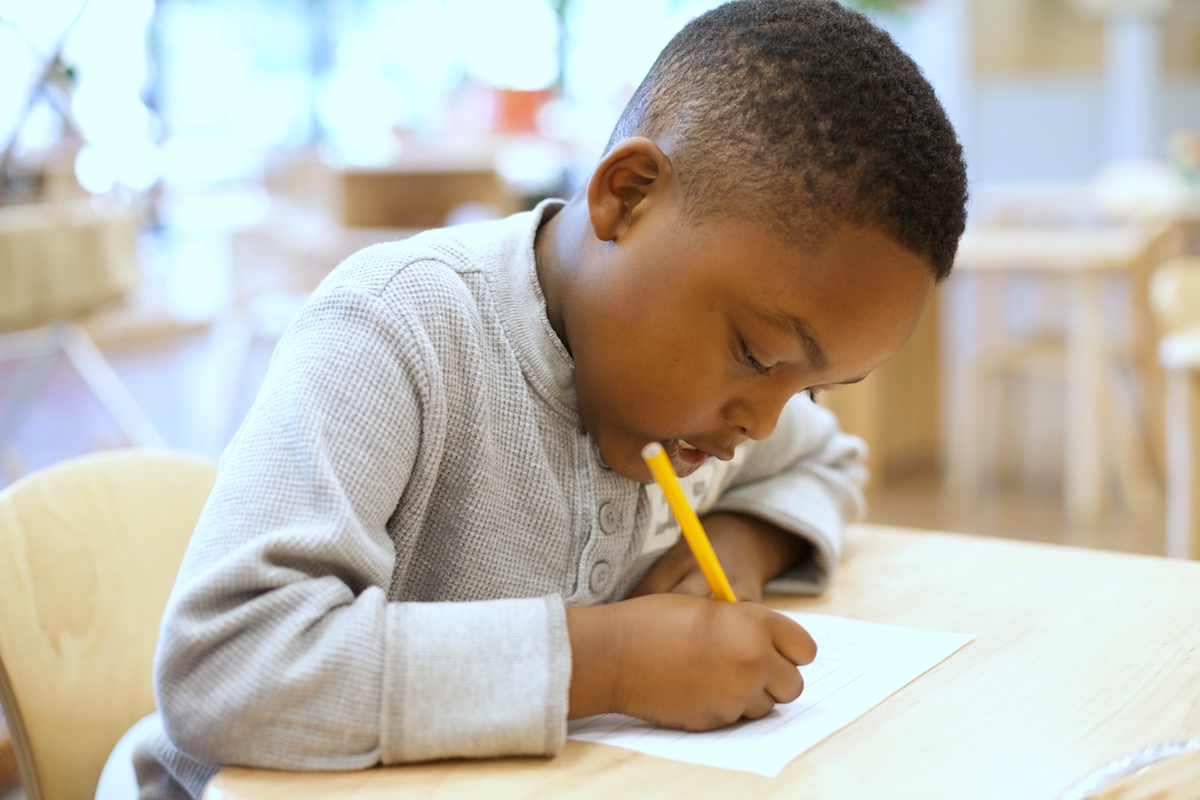

Manipulating a Pencil

Long before they are ready to write a story (or even a word!), Montessori children begin learning how to carefully manipulate a pencil. The metal insets are a beautiful material that were designed specifically to prepare the hand for writing. While the shapes in the material are reminiscent of a geometry lesson, that is not the primary intention. What’s meant to be the focus is the teaching of a variety of handwriting skills, including pencil grip, applying appropriate pressure, moving the pencil left to right, and further strengthening the muscles of the hand to build stamina.

Early Letter Formation

Montessori primary classrooms are equipped with a special material that helps children learn how to form letters. The sandpaper letters are wooden tiles with letters made out of a sand-textured surface. The children use their fingers to trace the shape of each letter, and later use the tiles as a reference while learning to write for the first time.

Another option for children to practice letter formation is to use their finger and ‘draw’ the letters in a small tray of sand. Both sand writing and using the sandpaper letters appeals to the sensorial nature of the primary child, making these activities fun.

Cursive or Print?

By the time a Montessori student is 4 or 5 years old they begin writing joyfully because they are well prepared. Montessori schools typically focus on teaching children to write in cursive, even in the primary classroom. We have found that there are many benefits to emphasizing this style over manuscript/print writing.

Learning to write in cursive has many advantages:

It’s nearly impossible to reverse letters in cursive.

Cursive writers can read print, but the reverse is not always true.

The ligatures in cursive may help early readers see groups of letters (oa, ing, th, and so on).

The flow of cursive words allows the writer to focus on the ideas of the writing rather than the formation of individual letters in isolation.

A Continuation

When children enter a Montessori elementary program, their teacher will emphasize the mastery of cursive writing and take the time to review any letters or skill gaps they may have. From here on, children practice constantly. They have notebooks they are expected to record their daily work in, and that work is expected to be written beautifully and neatly. Not only that, but the children themselves take great pride in the beauty of their own writing.

As time goes on, students do eventually learn skills such as keyboarding. Fortunately, they have been given a foundation that emphasizes the power of neat handwriting. In our fast-paced, shortcut-filled world, it’s nice to think that our children will grow up to enjoy sitting down to craft a thoughtful letter, using a pen, some paper, and their own hand.