Montessori is known for fostering academic excellence. While most people think of how we teach children reading, writing, and mathematics, you might be amazed to learn how we teach other subjects!

In Montessori classrooms (particularly elementary classrooms) the following subjects are referred to as cultural areas of study. They often overlap, as they do in the real world, and guides are adept at weaving language and math work into lessons as well.

It is important to note that while we do have a standardized cultural curriculum, our guides are specially trained to honor and support the personal interests of their students. This means some areas may be studied more deeply than originally intended, or they may end up branching off into other related areas of study in addition to typical lessons and materials. Doing this allows us to continually foster curiosity and internal motivation as young children grow and develop.

Science

When it comes to science in Montessori classrooms, biology is the main event. With work that spans basic biology as well as botany and zoology, we provide authentic points of interest by keeping living things in our environments. Our classrooms are home to both plants and animals, both of which are cared for by the children. When teaching various lessons in biology, guides often utilize living samples to increase interest and engagement.

Children in our primary classrooms begin this work by way of nomenclature. Card materials that double as reading practice help them learn the names of body parts of different animals. For example, one set of cards might include a picture of a horse with label, along with cards highlighting and labeling hoof, mane, tail, eye, ears, etc. Primary-aged children also get plenty of hands-on experience with botany learning; they cut and arrange flowers, they prepare various fruits and vegetables to eat, and many get a chance to garden and/or compost. They also learn the basic parts of plants, as well as the different shapes of leaves.

The learning continues into the elementary years, where students study the kingdoms of life on earth, differentiate between invertebrates and vertebrates, and study the external features and body functions of the five classes of vertebrates. Their understanding of botany expands and deepens, as they learn in greater detail how plants are formed, how they reproduce, and how they interact within their broader ecosystems.

In addition to their work in biology, Montessori students study a wide variety of other subjects in science. They learn about the scientific method, how to conduct experiments, and topics such as the solar system, chemistry, physics, and more. They attend lessons with guides, explore topics independently and with peers, and learn how to conduct research.

Geography

Montessori children learn to view geography as an interesting and multi-faceted area of study. Primary-aged children learn about the continents and biomes of the world using specialized globes, wooden puzzle maps, and other materials. During the elementary years this work is expanded significantly. Children learn about the different countries around the world, the cultures of the people who live there, and the animals who inhabit the various biomes. They also learn about landforms and bodies of water.

Beyond the surface of our earth today, our students learn about how it has changed over time. They are taught about the beginnings of our universe and how our planet was formed. They learn about the layers of our atmosphere and the layers of the earth itself. They explore the mechanics and functions of various natural occurrences around the planet, including how water (in all three states of matter) and wind can contribute to significant change over time.

Our hope is to give children a view of the whole world, and our work in geography serves as an impressionistic platform to inform them of the interconnectedness of everything on our planet.

History

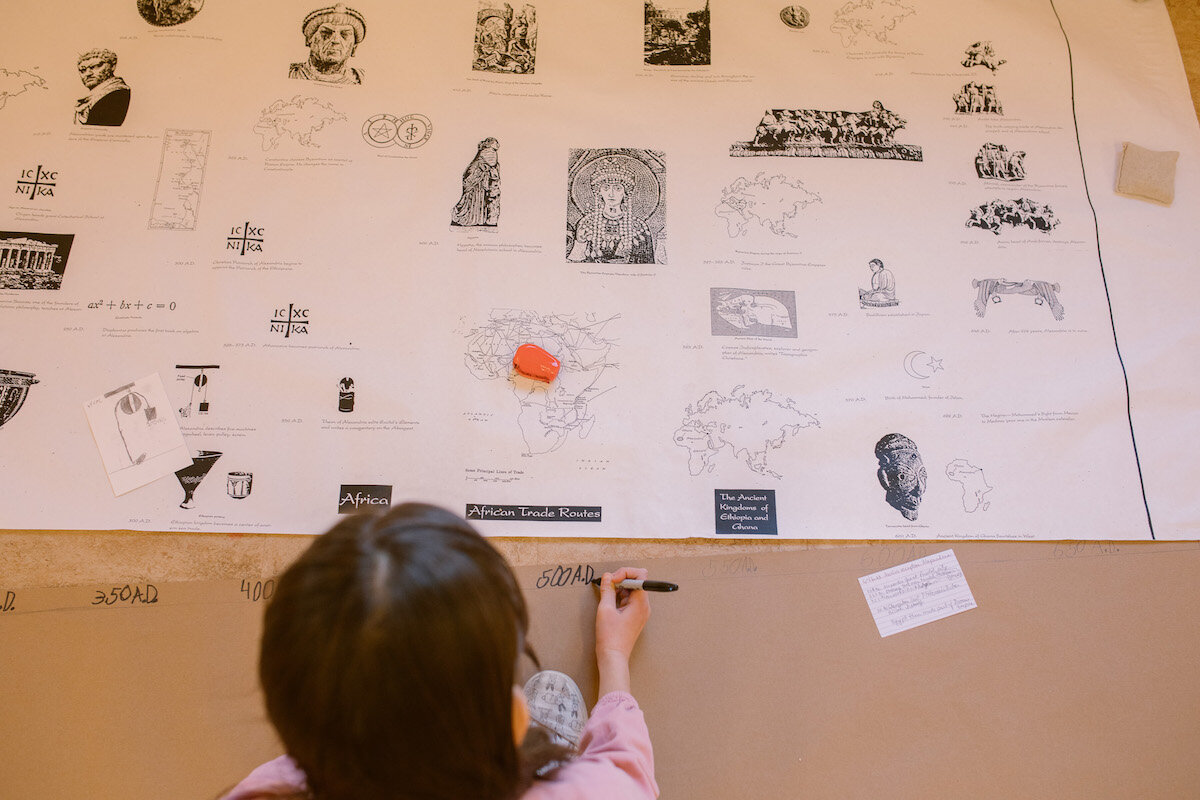

While the bulk of the history curriculum begins in the elementary years, primary children often have an opportunity to reflect on their own lives during our traditional birthday celebrations, as well as gaining an initial sense of the passing of time. They learn about the days of the week, the months of the year, and start to use a calendar together as a group.

Beginning in the first grade, we know that children are developmentally ready (and eager) to explore the concepts of history. As mentioned in our summary of the geography curriculum, we give our students a look at the history of our universe. This leads to a study of the evolution of organisms on Earth, as well as a look at early humans.

Our study of the history of humans branches off into many directions. After learning about the earliest humans, children learn about ancient cultures, the fundamental needs of humans, and how people in different societies have (and continue to) meet those needs. We explore the origins and history of mathematics and language, which children at the elementary level find particularly relevant and interesting.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these three subjects tend to overlap and connect quite a bit. Sometimes we guide children to discover these connections, and other times they recognize connections on their own.

Want to learn more? We believe the best way to discover Montessori education (or just to expand your understanding) is to visit our school. We welcome you to schedule a virtual tour. Today, we leave you with a quote from Dr. Montessori’s book, To Educate the Human Potential:

"…to give the whole of modern culture has become an impossibility and so a need arises for a special method, whereby all factors of culture may be introduced to the six-year-old; not in a syllabus to be imposed on him, or with exactitude of detail, but in the broadcasting of the maximum number of seeds of interest. These will be held lightly in the mind, but will be capable of later germination, as the will becomes more directive, and thus he may become an individual suited to these expansive times."