This article is part of a series that we will share throughout the 2020-2021 school year to celebrate the 150th birthday of Dr. Maria Montessori. Check back often for more posts that reflect on the past, present, and future of Montessori education.

The entire foundation of Montessori education is built on a legacy of scientific observation. As you likely already know, Dr. Montessori began her career as a physician with absolutely no intention of working in the field of education. Her earliest work in a psychiatric clinic led her down the beginnings of a path that would guide her work for the rest of her life.

She watched, she noticed, and she reserved judgement. From that first clinic, to the various other placements in Rome, to the first Casa dei Bambini, and all the other schools she helped inspire and create throughout her lifetime, she observed. As a scientist, she knew the value of approaching her work without bias, and with intent to collect meaningful data.

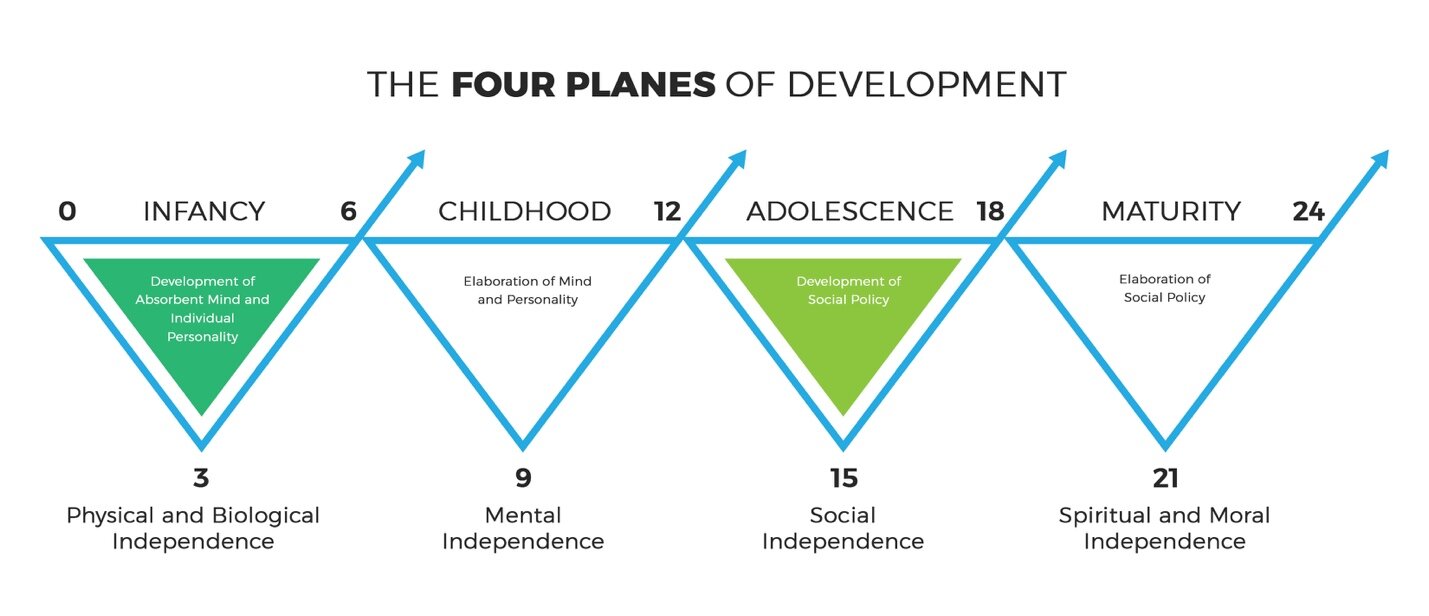

Over the years, Montessori began to notice patterns. Just like any one of us, she acknowledged that it is impossible to expect all children to fit into the same parameters, but she realized that there are very distinct characteristics that children of different ages tend to display. Regardless of location, culture, or language, she noticed commonalities emerging, and she used this information to lay forth the planes of development.

The general idea is that learning and development is not linear, but rather flows in cycles.

These planes of development are what guided the original groundwork for the various environments in Montessori schools. From the way we organize our classrooms to the way we present lessons, it’s important that everything we do is meeting the child exactly where they are. As Montessori guides, we use the planes as a guide while we plan, as well as how we approach children with their everyday work. We know that when families first learn about this information, it tends to resonate deeply as they recognize their own child and form a clearer vision for their child’s future.

The First Plane

Birth-6 years

“Help me do it myself.”

Montessori noted that there were distinct differences between the first and second half of the first plane. She called the child aged 0-3 the spiritual embryo, a concept that is not very dissimilar to what some people today refer to as the fourth trimester. Humans, unlike other organisms, need a significant amount of time after they are born to become fully developed. During these first three years, children’s bodies and minds grow in ways that allow them freedom of movement, as well as critical language skills.

How can we support infants and toddlers?

Create an environment that encourages rolling, crawling, standing, and walking.

When a child is old enough to walk, we allow them to do so (even if this means we slow down to meet their pace).

When your infant babbles, mimic their sounds in a conversation format. This will help them learn how humans communicate.

As our children develop more sophisticated language skills, engage in regular conversation.

Read and sing songs together frequently.

Support their practical life work. This means finding ways for them to independently meet their self-care needs, such as eating, drinking, toileting, and dressing. Of course, they will need full support as infants, but you can gradually nurture their growing independence as time goes on.

Montessori referred to the child aged 3-6 as the conscious worker. Children of this stage want to become masters of their environment, and their play(work) becomes a critical part of their development. The skills they developed during the first three years of life are refined and applied to their continuing development. Children of this age begin to develop their personalities. The way we support them is really continued work:

Allow young children to be as independent as possible.

Find ways for them to engage meaningfully and authentically in ‘adult’ tasks, like household chores.

Create an environment that allows for independent dressing, snacking, etc.

Continue to read and sing together as they refine their language development.

To learn more about the first plane specifically, visit Aid to Life.

The Second Plane

6-12 years

“Help me to think for myself.”

The second plane of development is a time of abstract ideas, great imagination, a deep sense of justice and fairness, and a strong desire to socialize with peers. Children of this age have an enormous capacity to learn about their world and universe, and their curiosity to do so is boundless. One of our greatest tasks is to provide extensive learning opportunities in the cultural areas of study (science, history, & geography) in order to meet these needs. They begin to think outside of themselves and are curious about the world and their place in it. How might we support children during these years?

Understand their desire to be with their peers and build social opportunities into each day.

Acknowledge that social skills are still being developed, and children will need guidance when solving conflicts.

Utilize this social time to create structures in which children can learn to work together cooperatively.

Provide plenty of books and other sources of information about areas of interest.

Note that children in the second plane have lost the sense of order they once had when they were younger. While we still need to teach them responsibility and cleanliness, it is completely normal for them to pay less attention to these things and become messier than they once were.

The second plane is a period of physical growth in which children sometimes become temporarily unaware of where their limbs are. This can lead to periods of general clumsiness, bumping into furniture or people, knocking items over, etc. Just knowing this can be a helpful reminder that it will pass.

It is important that we remember the great strides and capabilities children have in the areas of math and language during this time as well, and that each child will move at their own individual pace in these subjects.

We should continue reading with our children as long as they enjoy it (for many children this is into the early third plane) as we can model good reading while also dedicating time to connect with them.

To read more about the second plane, click here.

The Third Plane

12-18 years

“I can stand on my own.”

The third plane, in many ways, mirrors the first plane. True - adolescent children are much older and independent than young children, but they are on the cusp of transforming into adults. This is one of the greatest shifts during the course of a human life. While teens are going through big physical changes, they are simultaneously experiencing great internal changes. They have a deep drive to push away from their parents and become independent, yet they are not actually able to fully do so. These are important characteristics to keep in mind while we search for ways to support them.

Make yourself available. Even when it seems like your teen doesn’t want you around, they need to know you are there for them when they do.

Keep the lines of communication open. Your adolescent is able to discuss much more mature topics, and likely does with their friends. As adults, we can be the people they trust for facts, and we can teach them how to discern conflicting pieces of information on their own.

Encourage teens to follow their passions. This is a time in their lives when they will begin to discover their future paths. Our task is to support what they choose, even if that involves exploration of many options.

Support their emotional growth and changes. There will be times of upheaval, but there will also be times of great joy. They will need you there to listen.

Consider providing opportunities for teens to help out in their community. They will be searching for ways to connect and contribute, and they have the capacity to understand many of the struggles our society faces.

Allow adolescents to pursue authentic work whenever possible; this could be creating art, fixing old cars, getting a job or apprenticeship, or even starting a business. If a child is motivated and interested, we can guide them on their way.

What does this look like in Montessori schools? Click here to learn more.

The Fourth Plane

18-24 years

“I can achieve independently.”

As an adult, the early years are a time in which most of us develop a sense of purpose in a deeper sense than we had previously. We refine our goals, further develop our interests, and consider what we might do to contribute to our society. This often comes in the form of a career, but it can take on many other forms as well.

People in this stage are often working toward achieving financial independence - an increasingly challenging task in today’s economy. Luckily, young people are creative, and they find ways to meet their needs within the environment they find themselves in.

For more on what Dr. Montessori had to say on the planes of development, click here.