This article is part of a series that we will share throughout the 2020-2021 school year to celebrate the 150th birthday of Dr. Maria Montessori. Check back often for more posts that reflect on the past, present, and future of Montessori education.

There are many elements that make Montessori education stand apart from more conventional methods. One of the most obvious is our mixed-age classrooms. Rather than grouping children by a single chronological age, our classroom environments encompass children spanning across several ages.

We find this method to be a huge benefit. Read on to learn more.

But...why?

There are so many perks to having mixed-age classrooms. Some of the key points include:

Models and leaders

By having children of different ages together in one room, the younger children enter the environment with a variety of older children that serve as models to them. It is often the case that children learn best from one another, and when a 6-year-old watches an 8-year-old work, they quickly understand what is expected and what kind of work lies ahead in their future. As for the older children in the class, they have many opportunities to serve in leadership roles, cultivating skills that are critical as they become independent members of their communities.

Skill progression fluidity

Learning is not linear, for any of us. There are periods of rapid growth, periods of steady progress, and times spent in plateau. This is normal and will vary across subject areas for individual children. This is why we don’t believe it makes sense to deliver a prescribed curriculum to all students at the same time, ultimately leaving some children bored and others struggling. In our classrooms, kids can work and progress at their own rates. These lines are further blurred when we don’t rely on typical grade levels.

Strong relationships

When a child is in a class for three years, it allows the guide to really get to know them not just as a learner, but as a person. Rather than starting from scratch each September, the child-teacher-parent team is already established and can work together on a deeper level and with greater understanding of strengths and goals than they would be able to otherwise.

Enhanced social opportunities

Diversity is important on all levels, and that includes spending time with people of different ages. We have so much to learn from each other, and children gain all sorts of skills from their interactions in a mixed-age classroom, like empathy, patience, and open-mindedness.

Reflection of real life

We would be hard-pressed to find an example outside of conventional schools in which people are sorted into one-year age groups where they spend most of their day. Multi-age classrooms are a much better approximation of what life is really like, and we think children benefit from these early experiences.

What did Dr. Montessori have to say about it?

Maria Montessori had a way with words. While she was a woman of science who relied heavily on her observations, her descriptions and explanations often captured the heart of her audience. Her discussion of the multi-age classroom was no different.

“Our schools have shown how children of different ages help one another. The younger ones watch what the older ones are doing and ask all kinds of questions, and the older ones explain. This is really useful teaching, for the way that a five year old interprets and explains things is so much nearer than ours to the mind of a child of three that the little one learns easily, whereas we would scarcely be able to get through to him. There is harmony and communication between them that is not possible between an adult and such a young child. There is a natural mental osmosis between them. A child of three is also quite capable of taking an interest in the work of a five year old, because in fact the difference in their abilities is not that great.

People are concerned about whether a child of five who is always helping other children will make sufficient progress himself. But, firstly, he doesn’t spend his whole time teaching, but has his own freedom and knows how to use it. Secondly, teaching really allows him to consolidate and strengthen his own knowledge, which he must analyse and use anew each time, so that he comes to see everything with greater clarity. The older child also gains from this exchange.”

How we break it down

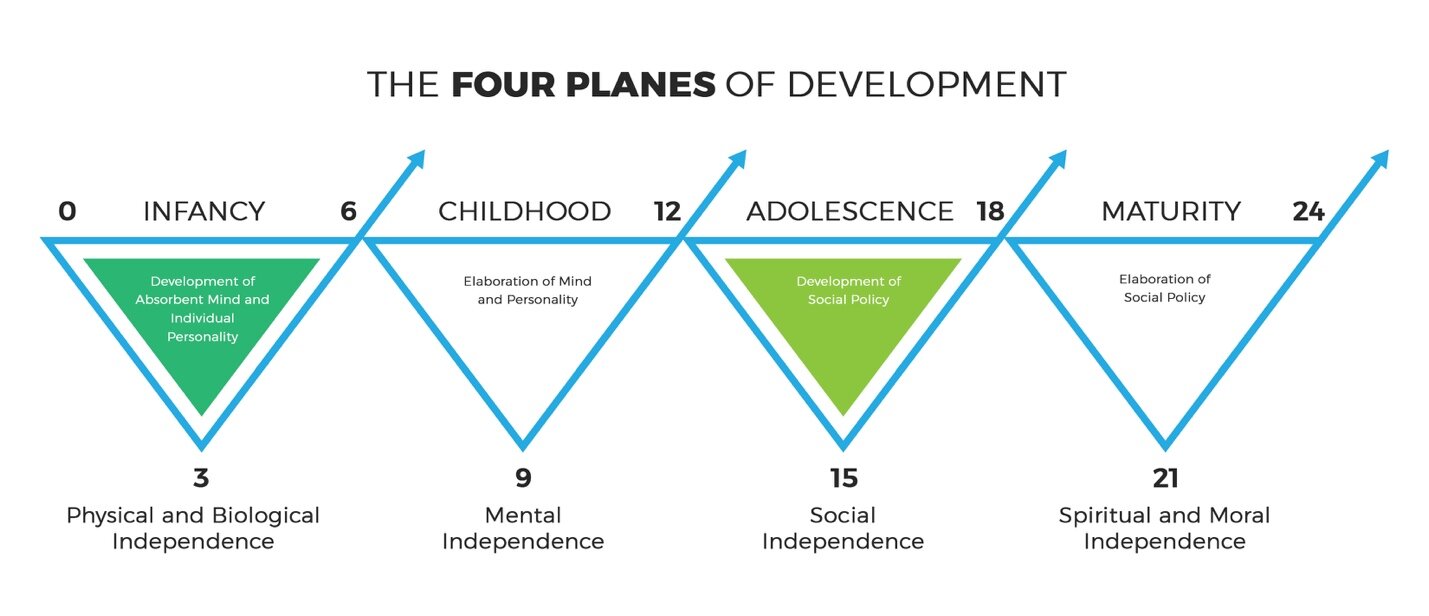

Obviously, a Montessori school doesn’t place a 3-year-old in the same classroom as a twelve-year-old (although we do love to find opportunities for children to work together from different periods of growth and development!). Generally speaking, the classrooms take on three-year age spans that roughly correspond with the planes of development.

Infant/Toddler - Sometimes divided into two separate environments, children aged 0-3 have specific (and similar) developmental needs.

Primary/Early Childhood - We combine what would be called preschool and kindergarten elsewhere, with children ages 3-6 working alongside one another.

Elementary - Many Montessori schools have a lower (ages 6-9) and upper (9-12) elementary environment, but others keep them combined.

Adolescent - As with several of the other age groups, teens aged 12-18 may be placed in separate middle and high school environments, or they may work together for all/part of their day.

Still have questions? Send an email or give us a call. We would love to chat with you about how Montessori serves children in a wide variety of ways.