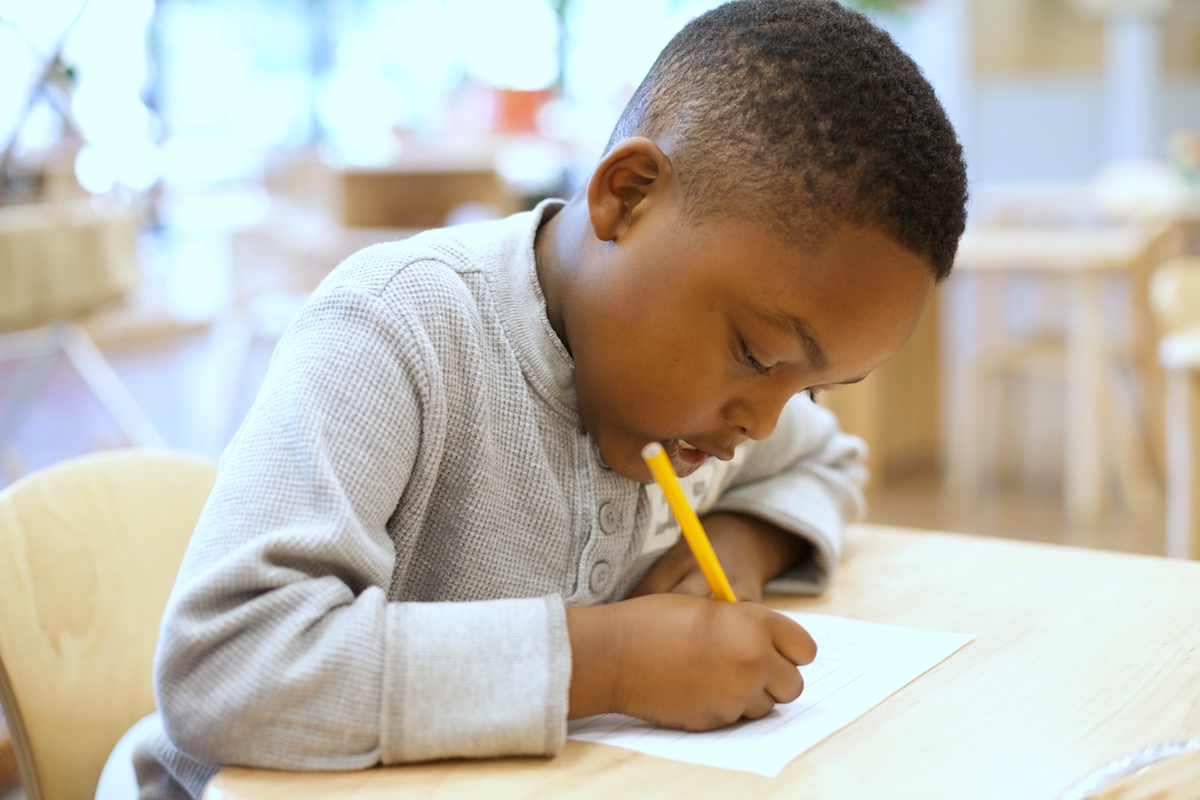

Montessori curriculum tends to give children opportunities to learn about fascinating areas of study very early in their school career. Science is no exception, and one major component of a Montessori elementary (and even primary!) education is the study of zoology. This post will highlight the content covered and how students typically explore the work.

Starting with the big picture

In the Montessori world, most areas of study start with the big, overarching picture and gradually narrow down to specifics. This gives children a firm understanding and context in which they can place the details. Zoology is no different.

What better way to teach about life on our planet than to begin with a look at the five kingdoms? Montessori children learn about monera, protista, fungi, plants, and animals. These early lessons are simple; they describe the major defining characteristics of each kingdom and give a few examples of each (with pictures, of course). One neat feature of this work is that the lesson can be given to younger children as they first begin to learn about zoology, but can be given again at a later age when children are ready to expand upon this knowledge. Science material that can be appreciated at different levels of learning is especially handy in a multi-age classroom.

Categorizing

After children learn about the five kingdoms, they begin to categorize the animal kingdom. The simplest way to do this is to define and sort the vertebrates and invertebrates. Children learn the evolutionary advantages to having a backbone, when the earliest creatures with spines began their life on earth, and which modern animals have one or don’t.

After mastering their understanding of vertebrates and invertebrates, children begin their study of the five classes of vertebrates: fish, reptile, amphibian, bird, and mammal. Once again, this work starts out simple but becomes more complex as time goes on and the child’s knowledge base expands.

A layered curriculum

A six year old’s study of reptiles will look very different from the study of a child just a year older. The six year old will likely be at the word level of reading and learning (especially early in the year). They will learn that a turtle has a head, feet, tail, and a shell made up of a plastron, carapace, and bridge. You may have noticed that some of these words are quite familiar, and some are most likely brand new and fascinating to the child. On the other side of the table our seven year old will be studying the body functions of the turtle. They will discover how the turtle meets its needs for movement, protection, support, circulation, respiration, and reproduction. This will include information such as the reptile’s three-chambered heart, the fact that it lays leathery eggs, and that it uses lungs to breath in oxygen.

Older students may review this information by playing classification games and asking one another questions (much like a scientific version of the game twenty questions). They may conduct research on animals they find particularly interesting, which gives them opportunities to explore their own work, learn how to research properly, write a short report, and gather more zoology information. Eventually they will go on to more deeply explore invertebrates and their contributions during the evolution of life on earth as well as what they look like and function like today.

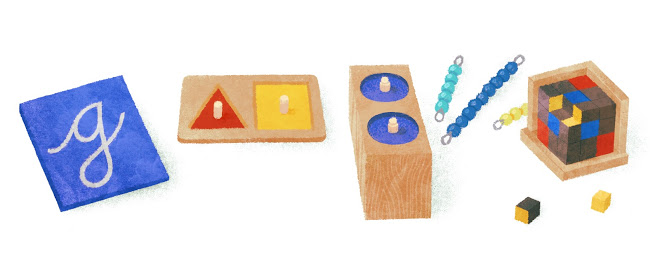

What are three part cards?

Many areas of study in Montessori classrooms utilize three part cards, particularly in primary classrooms. While studying zoology, children will use this style of material as they work to define the five classes of vertebrates. What, exactly, are they?

In the primary classroom, a set will include cards with pictures, cards with labels, and a control card that displays the picture with the label so that the child is able to check their own work. While something similar may be used with students just entering the elementary level, three part cards at this level tend to look a bit different. They generally consist of a picture, label, and definition. While there is a control available as well (often in the form of a booklet or wall chart), the elementary-style cards provide a higher level of reading opportunity so that the child is able to practice multiple academic skills within the same work.

The beauty of three part cards is that children are drawn to them, they have built-in controls that foster independence and self-teaching (after the initial lesson), and a teacher observing a child using them can quickly discern the child’s level of mastery

Extensions and more...

As mentioned before, studying zoology lends itself seamlessly to research projects for older students. Students of all ages can benefit from art integration as a means of reinforcing concepts while expressing their creative side. For example, a collage of a fish’s body may be made, which may then be turned into a labeled diagram.

Did you know that the Montessori study of zoology directly ties into large parts of the elementary history curriculum? Many of the animals the children study in their science lessons can be found on the Timeline of Life, which is a beautiful and impressionistic material that teaches children about the evolution of life on earth. Starting with the beginning of the Paleozoic era, in which one-celled organisms and simple life forms floated through the sea, through the Quaternary period and the emergence of early hominids, children are able to see the connections between the various kingdoms and classes, bringing the details of their learning back to the big picture again.