“A child learns to adjust himself and make acquisitions in his sensitive periods. These are like a beam that lights interiorly or a battery that furnishes energy. It is this sensibility which enables a child to come in contact with the external world in a particularly intense manner. At such a time everything is easy; all is life and enthusiasm. Every effort marks an increase in power. Only when the goal has been obtained does fatigue and the weight of indifference come on. When one of these psychic passions is exhausted another area is enkindled. Childhood thus passes from conquest to conquest in a constant rhythm that constitutes its joy and happiness.”

Dr. Montessori spoke and wrote about her discovery of what she called sensitive periods for learning. Simply put, they are periods of time in a young child’s life in which they are primed to practice and master certain skills. During these sensitive periods, a child craves this practice intensely, and can concentrate on the work deeply and in ways that sometimes surprise us as adults. Once they have engaged in enough repetition over time, they master the skill, become bored, and move on to whatever is next.

Montessori’s sensitive periods stretch throughout childhood. It is important to recognize that learning is not linear or standardized. Different children will arrive at different developmental stages in their own time. What Dr. Montessori did notice were strong patterns among the children she observed. The following is a guide to what you might expect:

Birth to age 1

Sensory learning

Babies interact with their environment in an effort to refine their many senses. This learning continues throughout early childhood, and Montessori classrooms are equipped with specialized materials that appeal to the child who is seeking such practice.

Verbal language

In the early months of a child’s life, they are listening to the language of others around them, attempting to make sense of sounds, patterns, and inflections. They derive meaning from the speech of those older than themselves even before they are able to speak.

Ages 1 to age 4

Continued sensory learning

Development of speech (typically until around age 3)

We all know and love this stage! Toddlers work so hard to communicate verbally for several years, eventually getting to a point where they can be understood. Afterward they continue building vocabulary.

Continued verbal language

Motor coordination (both fine and gross)

From body control and movement (running, jumping, skipping…) to manipulation of small tools (think holding a pencil, cutting with scissors, sewing, etc.), these three years involve a lot of work on the child’s part! Their bodies are growing, their muscles are developing, and they are generally having a blast in the process.

Ages 3.5 to 4.5

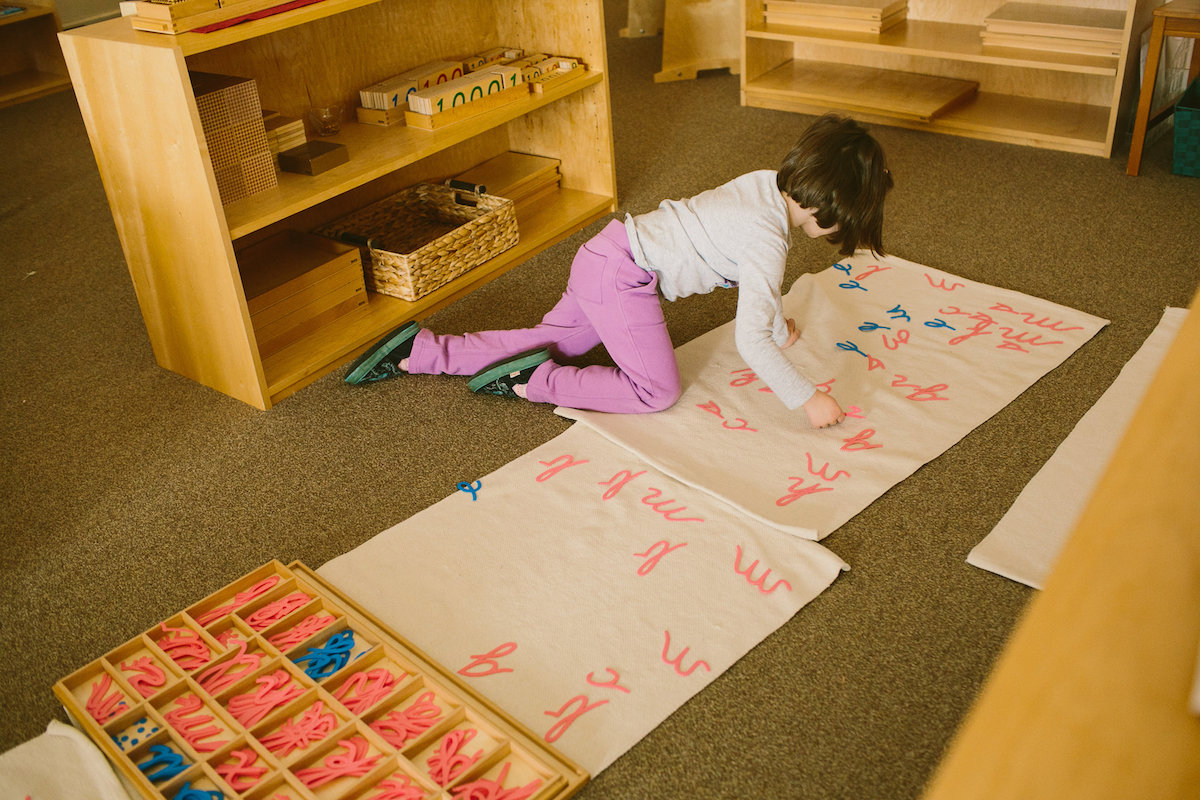

Writing

Children at this age are ready to begin the work that will help them become writers. They will learn to hold a pencil properly, to draw lines carefully and intentionally, and to form shapes that lead to cursive and print letters.

Ages 4 to 5

Continued sensory learning

Continued verbal language

Continued motor coordination (typically until shortly before age 6)

Reading

At the beginning of this sensitive period, the child is understanding sounds and blends. They then move on to reading simple words, more complex ones, and eventually stringing them into sentences (which may come a bit later).

Mathematics

During this time the child is preparing to learn basic math skills, and eventually mastering them. They develop a sense of numeration, place value, and operations, among other important skills.

Ages 6 to 12

Social development

During the primary years children often engage in what is referred to as parallel play, when they sit beside one another but focus on their own agenda. In the elementary years, there is a definite shift; children crave the company of their peers. They want to sit together, talk together, work together, and learn from each other. They learn the many benefits of friendship while also developing skills to resolve conflict and work together as a group. They learn the delicate balance between the needs of the group and their individual needs.

Understanding and interest in justice and morals

When children at this age have recess time, adults commonly report that most of the time is spent by the children developing the rules for the game, with far less time being used to play the game itself. They are very interested in making sure things are fair, and they are at the perfect age to learn about character development and how we should treat one another.

Imagination

Children at this age use imagination not just as a fantasy world, but as a vehicle in which to place facts. Storytelling used to teach information is particularly useful at this time.

Interest and understanding in human history and culture

Now capable of thinking of more than themselves, elementary-aged children are keen to learn about the origins of humans and the various ways we live around the world and have lived throughout history.

Interest and understanding of the history and evolution of the universe

Much like their interest in humans, children at this age are curious about the universe and everything that resides in it. They are fascinated by creation stories, both those told from a modern scientific perspective and those that reflect historical cultures around the world. They are also the perfect age to learn about the evolution of life on earth.

As adults, our task is to be aware and supportive of children’s sensitive periods. When we notice the deep focus or repetition beginning, we can give children the space, time, and support they need to practice and engage with whatever skill they are working on. We must let the magic they’re feeling ignite while they learn, for once a sensitive period passes, the child will likely never feel quite as motivated in that particular area again. Montessori classrooms strive to create environments that guide children to dive deep into their sensitive period work, no matter how old they are.

Curious to see what this looks like? Contact us for a tour today!