As parents today we are bombarded with advice, ideas, suggestions, and rules on how to be the best parents we can be for our children. Some change is good; emerging research tells us more and more about human development and how our brains work, and making progress as a society is always a good thing. Still, it can be hard to weed through the good ideas and those with good intentions that don’t really serve us or our children.

Giving children choice is important. Respecting children as autonomous human beings is important. We should recognize that even though they are young, their lives are not ours to live. Their dreams are not ours to fulfill.

So, we give our kids choice. We let them make their own decisions. We honor their growing independence and understand that their ideas may sometimes (often) conflict with our own. And we try to be okay with that.

But should we let our children do whatever they want all the time? We would argue that no, that is a very different scenario. Giving choice is one thing, neglecting to set any boundaries is something altogether different.

What do children need?

In order for a child to strengthen their sense of independence they need to be able to make their own decisions, but they need to make these within a framework that feels safe. As kids learn and grow, they need to be able to take risks and make mistakes; after all, making mistakes is one way we learn. It is critical, however, that we keep give our children boundaries within which they are able to make choices.

As children grow and develop, it is critical that they form bonds with adults in their lives that are trusting and secure. Our kids really do test us sometimes; they push against the rules we set because they are seeking a sense of how strong our limits are and whether or not we mean what we say. Giving guidance and setting boundaries isn’t just okay, it’s critical to letting our children know we are here for them and care about their well being.

In short: kids need choice. They also need those choices to fall within limits that keep them safe, both physically and emotionally. When they’re younger, they need fewer choices and more limits. As they grow, we increase the choice and decrease the limits. This way, once they are fully mature adults, they have had plenty of time to practice making decisions prior to any expectation that they actually do so successfully on their own. Isn’t that what childhood is all about? Human children are able to experience a joyful period of time in which we get to practice becoming a responsible adult.

What does this look like in our classrooms?

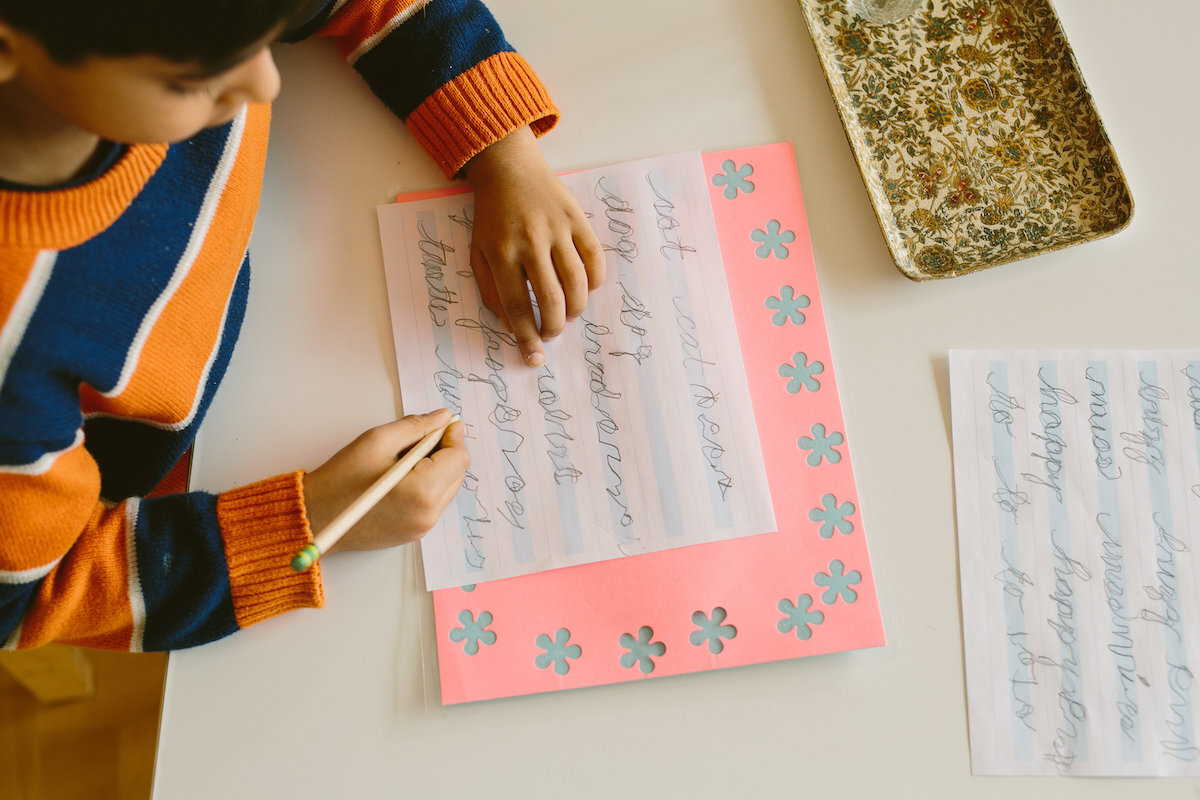

Montessori classrooms are carefully prepared environments with built-in choices and limits. Some examples of how we achieve this balance:

Furniture is arranged so that children are free to move around, but most classrooms are devoid of large open areas that might encourage running in such a confined space. Those shelves are placed with intention!

Materials on the shelves are rotated frequently. Children may only access what is available to them. Materials that we do not want the children to have access to are kept stored away in a cabinet or closet.

The snack table might be just large enough for two chairs. We want children to eat and socialize when they choose, but we also know that if there is space for ten children to do so at once, the activity may become disruptive and lose its original intent.

Older children may utilize work plans. This enables them to determine the pace, order, and details of their work, but requires them to be accountable for completing all desired tasks within a specified amount of time. For example, a child may be asked to complete a range of math, reading, and biology work within a given timeframe, but there is plenty of choice in how they accomplish the goal.

Children in Montessori classrooms do not typically have to ask permission to use the restroom. Instead, we create structures so that they may do so safely whenever the need arises. Some schools have restrooms located within the classroom, others have hall passes available, or hold class meetings to discuss procedures with the children.

What might this look like in our homes?

If your family is new to Montessori, it can sometimes take a bit of time to shift ideas and expectations. Once you do, however, it’s hard to imagine doing things any other way. Some ideas to get you started:

Allow your children to make decisions about what they wear. For older babies and toddlers, this may be as simple as allowing them to choose between two different color shirts. For older children, you may just set guidelines, such as their clothing must be appropriate for the weather.

If you need your child to get a few things done, let them choose the order. For example, ask them if they would rather take a bath or make their lunch first. Be clear that your expectation is that they will do both, but that you value their opinion and want to let them help decide how to spend their time.

Define boundaries when your child is struggling with emotions. It’s great to let your child feel whatever they are feeling, but that doesn’t mean they should mistreat those around them when they are frustrated or angry. “I see that you are frustrated. It’s normal to feel that way but you may not scream in our house. Here are some other ways to express that feeling…”

Have frank and open discussions with your older children. Have you been feeling like they’re overdoing it with video games or staying out too late? Tell them what your concerns are, what your limits are, and solicit their ideas with solutions. Rather than implementing sudden new rules, engage your older children in problem solving talks until you come to a conclusion you can both live with.

We hope this post has been helpful and inspiring. In a world of permissive parenting and misunderstandings about what Montessori really means, it can be easy to get caught up in giving in to our children’s every desire. The good news is, you don’t have to. Our children look to us to be the adults in their lives. Each and every child deserves adults who love and respect them for who they are.